Nikolay Georgiev ’44: The Humble Class President

1August 30, 2016 by American College of Sofia

Nikolay Georgiev at home, March 2016

Interview by Petia Ivanova ’97

It wasn’t difficult to persuade Nikolay Georgiev to put time aside and share some of his memories from the old college days with me. However, as the agreed-upon day for my visit approached, he started calling me to “warn” me that his life wasn’t that worthy of attention, that his memories were merging into one another and fading and it would be difficult to separate and put events in chronological order. Wouldn’t I be disappointed? I knew from previous experience that there was no way the story of an American College graduate that has lived through three very different time periods would disappoint me and indeed, on the unusually warm March day of our interview, I left his cozy flat on Vitosha Blvd. anything but disappointed. I was grateful and immersed in thoughts. Nikolay Georgiev turned out to be an unnecessarily humble former class president and valedictorian who became a long-standing translator of “humanitarian” prose – as he called it – in three (!) different languages. What makes us so stubbornly refuse to be called “artists,” if we aren’t Picasso, I asked myself. After all, isn’t translating the creative work of others to another language, without losing the richness of the original, creative work in itself, and isn’t one who does it well an artist?

My Father, Foreign Languages, and the College

My father was a merchant. He mainly imported toiletries, cosmetics, and shaving accessories from Germany. He was the one who insisted that I study foreign languages. I got my primary and junior high school education at the German School, then I studied at the American College. It was an obsession of my father’s that I study foreign languages because he himself didn’t know any and regretted it; it was as if he wanted to fill this gap through me. At work, he had an assistant of German origin that he traveled everywhere with, like the Leipzig Fair they went to twice per year. Sometimes my mother, who spoke French, joined him and twice he took me as his translator. One of those trips took place shortly after I had started studying at the College, so we asked the director’s permission for missing classes – it was after the start of the school year.

As a merchant, my father traveled all around the country by train before the war, carrying suitcases full of samples. In fact, he built this very building. We moved in right before the bombings on 10 January 1944 and we had to evacuate it soon after that. We were able to return only after 9 September 1944.

Nikolay in the 1940 Yearbook

In 1938, 60 boys and 40 girls entered the College. The families of most of the students were well-off. The tuition fee was 24,000 leva per year. There were students on scholarships like Chocho, who rang the bell, or the students working in the cafeteria. There were many Jewish students and, in spite of the whole Bulgarian chest-thumping for having saved all our Jews during WWII, there was a perceivably negative attitude in the country towards Jews while the war lasted. Whether it was a state order, I don’t remember, but Jews did wear stars here, as well, and some were forced out of their homes. On account of the families of Jewish college students leaving the country, the size of our class decreased significantly during the war.

I recall being the class president, like a representative, in second form. I was chosen solely for my excellent grades but, let me tell you, those are no indication of how successful one will be later in life. I was on the Bulletin Board, with the fourth highest GPA in the whole school. I remember I had to address my classmates at some gathering in Assembly Hall,  but I felt so ill-prepared that I don’t think I managed my task. Vicho Mehandjiev, the class secretary, was more ambitious and such a representative function would have suited him better.

but I felt so ill-prepared that I don’t think I managed my task. Vicho Mehandjiev, the class secretary, was more ambitious and such a representative function would have suited him better.

I wasn’t much of an athlete, nor was I especially active in extracurriculars. I possessed average intelligence but I was good at studying. And once you become a diligent student, much like with a handwriting style, you’re stuck with it: you can’t just shake it off, so you keep it up out of habit. It’s as if I was expected to be a good student, so I was living up to the expectations. That’s just how things turned out.

I’ve had classmates make fun of me or throw slighting comments my way, too. Once I got in a fight with another student, a year older than me, Naum Georgiev, and I ended up with a crooked nose. That was in my first form year and he had been relegated to our class. We fought near the bedroom sink, but what for I don’t recall anymore. I doubt there’s anyone who never got into fights at that age.

The truth is I started off with F’s in German both terms the first year at the German School, and my parents saw fit to hire a private tutor (for my sister and me), a German lady named Olga Balkanova, married to a Russian officer who had left Russia. She was very, very good, and had a perfect command of French, too. She saved me and I acquired a solid base and confidence thanks to our lessons. That’s how I became a good student and then remained that way to the end of my studies.

It’s interesting that even now I speak German – the language I studied first – with greater ease. My second foreign language was French. From the start and all the way through my studies, I learned from very good professionals. The second foreign language teaching at the German School was very in-depth and lasted three years. After that, I continued at the College with Mr. Hristoforov and Mr. Berlan, a Frenchman who had came to Europe after spending years in Africa.

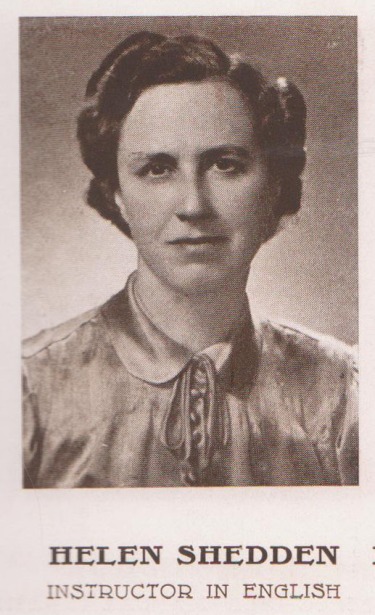

This here (pointing at the 1940 yearbook) was our first English teacher at the College, Ms. Helen Shedden. We studied English very intensively, 12 hours a week. I remember Ms. Shedden asking to see me in private somewhere around the middle of the first term to ask me to help a classmate, Tsvetan, who was having trouble with the language. This was a turning point in my English language career.

Generally, the College had a very good teaching staff. I remember my teachers very well; they live on in my mind. Benjamin Stolzfus taught us history of religions and psychology,

Konstantin Zlatanov, instructor in math, 1940 Yearbook

Mr. Panayotov taught history and Mr. Yankov was one of the senior administrators and taught math, as well. Mr. Bliss, who taught the other class, was the best English teacher. Our math teacher Mr. Zlatanov[1] was, to me, made of gold. It didn’t matter that he gave me my only grade other than an A+/A – it was an A-. In fact, I don’t hold any grudges against any of my teachers. I was a diligent student, so what grudges could I possibly hold!

I remember how we younger students looked up almost in awe to the older ones; we knew their names and faces well. I knew very well who Petko Bocharov was, even though we didn’t meet at the College, as he graduated in the spring of the year I joined the College in the fall.

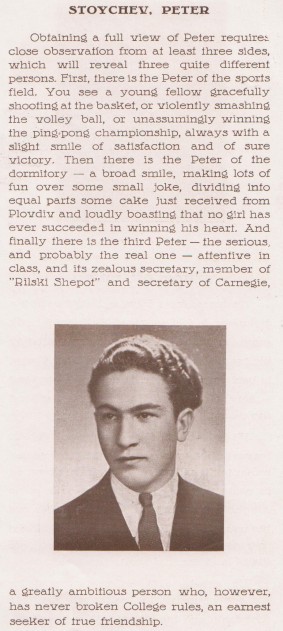

At the end of each term, we had to pass exams in all subjects in which our grade was lower than an A-, or was it a B, I don’t remember. I, on the other hand, with my straight A’s  across the board, could leave a week earlier for the Christmas holidays – this was my greatest joy of all. Together with the three years older Peter Stoychev ’41, I would get a cab in the evening and we would be home a week before everyone else – a major affair!

across the board, could leave a week earlier for the Christmas holidays – this was my greatest joy of all. Together with the three years older Peter Stoychev ’41, I would get a cab in the evening and we would be home a week before everyone else – a major affair!

In 1940, the last Bor Yearbook came out. The father of the College student Konstantin Kokoshkov, a friend of mine, was the director of the state printing house where the yearbook was printed.

After the Americans were forced to leave in 1942, Ivan Dyakov, an ELL teacher who had

come to the College from America, took over as the school’s director. I recall going to him with two of my classmates and friends in our last year at the College when it was just a few of us left, and asking him to transfer us and two more boys from the bigger dormitory bedroom to the smaller one. We were happy and a little surprised that he agreed.

Little did we know when we left for Christmas vacation in 1943 that we wouldn’t be returning to campus after the holidays as usual. Instead, the second semester was canceled because of the bombings and evacuations and it was only in July that we returned to get our diplomas issued by the State Co-ed Foreign Language High School in Simeonovo. Our class had been the last to follow the original curriculum, but there were just 15-16 of us who stayed on till the end in spring 1944. The rest had spread out to various schools in Sofia and the country.

Life and Career after the College

After the College, I did basic army training as part of the First Artillery Regiment. The compulsory military service used to be 2 years. In the army I met a lot of young men like myself – my brothers in arms – and one of them, Ivan Bidikov, got a job as an administrative secretary at the Union of Bulgarian Artists after his military service. When my five months of training were over, I was appointed at the War Ministry in the department responsible for communication with the Allied Control Commission. Мy first assignments had to do with meeting Russian, American, and British soldiers arriving at the train station.

Next, I enrolled at Sofia University with two majors: Law and Industrial Chemistry, the latter as an attempt to please my father by staying close to his area of expertise. There was a member of the Communist Party responsible for overseeing our neighborhood. His name was Mircho and he made sure I got expelled from the university in February 1949. Looking back, I see he was not all evil – for instance, he didn’t go all the way and kick us out of our home and city, which was our worst nightmare. It happened to relatives of ours.

As an expelled student, I was not allowed to stay unemployed, so I got a job as a construction worker at the high voltage plant site near Iliyantsi. I used to take the tram to a point and then walk to the construction site. On my way, I used to recite aloud two soliloquies: from Hamlet “O, what a rogue and peasant slave am I…,” learned in rhetorics class with Dr. Floyd Black as coach, and from Le Cid by Corneille “Percé jusques le fond du coeur d’une atteinte imprévue…,” learned in Mr. Berlan’s French class.

The construction site manager at Iliyantsi, engineer Nikola Govedarski, was a man from the old school, and he put me and two other young men like me in his office to work on administrative tasks.

At the beginning of 1951, my military service mate Bidikov, whom I mentioned earlier, found me and helped me get an office position at the Union of Bulgarian Artists. I worked for about 15 years as an accountant there, in spite of my bad reputation as an expelled student. At some point, those expelled for political reasons were offered a chance to enroll in a university with a major connected to the field they were currently working in; this is how I majored in accounting, something I found totally uninspiring. I studied by correspondence for 5 years, because I was working full-time at the UBA. I was quite happy with my colleagues and the community there. I knew about 700 Bulgarian artist-members of the Union by their three names. Many of them I knew personally, from Dechko Uzunov (Bai Dechko to me) to the youngest ones in the applied arts.

In 1965, I transferred to the Bulgarian Artist Publishing House as managing editor for translations. I stayed there until the end of my working career. We published a lot of multilingual summaries of texts in English, French, German and, less often, in Russian. I myself have privately translated about 70 books, and aside from that I have edited a great deal more. We had very good translators of all four languages. Oftentimes, I worked with Gerda Minkova, the German wife of Prof. Marko Minkov who taught English Philology at Sofia University. Gerda was a very conscientious translator and such a refined human being. Some of the German translations, especially those of children’s books, were given to another talented translator, Lotte Markova.

In the early years, I mostly translated from German and French. I started with Van Gogh’s letters in two volumes. If those were given to me now, probably something totally different would come out because it was an abbreviated version, a selection from a vast original material. I followed the German edition, but not entirely, adding many texts from the French original – you know, from Paris to Arles and to the end of his days Van Gogh wrote almost entirely in French. The 50,000 total print copies of the two-volume edition, which included a special leather case, sold out in just two days. Only the non-fictional biographies that French author Henri Perruchot wrote on Cezanne, Renoir, Manet, Gauguin, Van Gogh, Lautrec and Seurat – most of them also in my translation – could compete with that success.

Not everybody was happy with the result of my first editing assignment, as some found I was intervening too much. I may have overdone it, I don’t know. I recall how we got a translation proposal by a certain Emilia Georgieva, a singer by profession, who had emigrated to Italy when she was young and had studied Art History there. After her singing career was over, she translated a work[2] by Prof. Giulio Carlo Argan, a distinguished Italian scholar, writer and art historian, and sent us her translation. I did not like her work very much, so I rolled up my sleeves and started editing. I worked a whole year on this and I even put my name next to hers, well, after hers, of course, as a translator from Italian. I still have that book on my bedside table as a mental exercise of some kind. When reading it now, I find some of the passages hard to understand. You can’t imagine what language, what precision of argument, and what means of expression Argan employs! Every conclusion and judgment is reached with uncompromising strictness, which isn’t in our culture yet. This book, nevertheless, brought me immense satisfaction, the kind of satisfaction that comes with work well done. The Union of Bulgarian Translators awarded me for it.

Upon my retirement, I gradually transitioned to translating from Bulgarian to English language, which requires more effort and browsing dictionaries and other reference books. I’ve been subscribed to The Еconomist for 15 years now – a publication for exemplary English prose.

Keeping in Touch with Former Classmates

Sava (Savchev ’44) and I speak on the phone once in a while; we usually touch base when we get a message from the College. I think the last time I saw him was at the ACS Christmas alumni reception a year and a half ago. Young alumni picked us up and gave us a ride, which was very kind of them.

Sava Savchev ’44, ACS staff member Natalia Manolova, and Nikolay Georgiev ’44 at the annual Alumni Christamas Reception, 2013

On Hristo Belchev St., very close to where I live, lives another classmate of mine, Dimo Boychev. Somehow Dimo and I did not keep in touch.

What else can I say? I am almost 92, I’m not up for cultivating friendships. I did not start a family in my lifetime. There were a few disappointments, then inertia, and that was it. I never felt lonely though, because my sister and her family lived in the same apartment with me. Till the very end she stayed close to me; she died about a year and a half ago at the age of 94.

I never thought I would live that long. When I was young, I tried imagining what it would be like to live to the year 2000, when I would be 76. This seemed rather improbable. But medicine is different now; many times even cancer can be healed if diagnosed early enough.

I still go out, but just 2-3 blocks away. (Leaning on his cane, he gets up to make coffee: Italian coffee maker, incomparable!). I try to go out at least once a day.

My nephew, my sister’s grandson, applied to the College quite a few years ago, but was not accepted; he was so disappointed. Now he is 27, finishing a master’s in Cultural Studies. His thesis is on a topic from medieval history, and I helped him recently with a translation from German of a text about a medieval heretic, Marcion.

“Let me show you something interesting!”

With a mysterious smile, he fetches a black-and-white family portrait off the wall and asks me whether I can see a familiar face in this photo. I browse the image and exclaim upon recognizing no other than Ivan Vazov! It turns out Nikolay’s grandmother is Anna Vazova-Pacheva, Ivan Vazov’s sister, and Saba Vazova, their mother, is also in the photo. I reluctantly promise Nikolay not to share this so that it doesn’t sound like he is bragging about it, but secretly hope that he will change his mind until this gets published, and he does.

What else to say except that every relatively long life inevitably flows through many changes and mishaps. There are hardships, yes, but the passage of time tones them down.

You know, I was initially nervous about this visit of yours. I’m not used to occupying people with myself, but somehow I felt at ease and opened up. You should know that there is no other school in Bulgaria, surely not a high school, with traditions such as those of the American College. No one else does things like what you’re doing right now, reaching out to older generations and being genuinely interested in our stories. Thank you!

Thank you, Nikolay!

[1] Zlatanov comes from ‘zlato’, the Bulgarian word for ‘gold’.

[2] The Bulgarian title of the book was „Изкуство, история и критика” (Избрани студии и статии).

[…] wasn’t a very good student and have never been on the Bulletin Board for instance, unlike Kolyo (Nikolay Georgiev, read his story here) of my class, always heading the list. I wasn’t on the list at all, not even at its bottom. I […]

LikeLike